Soul: Three Curators, Three Ways |

|

A visit to Albuquerque’s National Hispanic Cultural Center Art Museum, 516 ARTS, or Santisima (an art gallery in Old Town) replenishes. These galleries are much more than rooms to house art–they inspire communities. This is because of three curators: Dr. Tey Marianna Nunn, Suzanne Sbarge and Johnny Salas. A curator is the head of a museum or other collection, an exhibition organizer. The word has a deep history. Curating can mean caring for all sorts of collections, from manuscripts to birds. According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, a curate is also the one who has “the care of souls.” How do all three of these curators consistently create magical experiences for their audiences? Not surprisingly, they all think of curating very creatively.

|

|

Tey Marianna Nunn For Dr. Nunn, “art comes alive” when she knows the artist, the place, the context of where it is made. She knows deeply that all three are intertwined–the daughter of professors, she travelled Latin America as a young girl, speaking to artisans all along the way. One of her favorite projects at the National Hispanic Cultural Center (NHCC) was “Meso-Americhanics (Maneuvering Mestizaje) de la Torre Brothers and Border Baroque.” Nunn encountered the de la Torre brothers’ work as one of the first participants in the Latino Studies Fellowship Program at the Smithsonian, created to offset their report, “Willful Neglect : the Smithsonian Institution and U.S. Latinos.” This fellowship helped Nunn realize that established institutions do not address the experience of Hispano/Latinos. Nunn vowed to return to New Mexico and “make a difference.” Nunn found the de la Torre brothers’ monumental blown glass, multimedia work complex and political, informed by their dual nationality as citizens of the U.S. and Mexico. Upon her appointment at the NHCC, they were the first artists she called, and their exhibit was extremely well received by all ages. |

Sandra Cisneros |

|

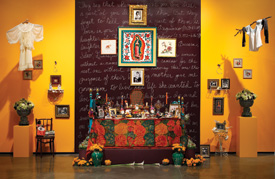

Nunn strives to overcome the way curators sometimes work, as elites with specialized knowledge. Instead, she works to convey the meaning of an exhibit to the public, telling artists, “you are the ones who have all the stories,” making the entire process of selecting and displaying their art a dialogue. The NHCC has a mandate to represent Hispano/Latino artists from New Mexico, the US, and around the world. Nunn takes a very ethical position, reminding her interns that curating has ramifications that can change artists’ lives: their reputations, their incomes. At the NHCC, she created a community arts gallery, because there are thousands of Hispano/Latino artists in New Mexico still often not exhibited anywhere. An incredible outpouring of community support means the community gallery art openings are the biggest at the NHCC. Nunn is also excited by her upcoming international exhibitions, especially one centering on Chilean Arpilleras, three dimensional applique collages, a way women express their political realities in silent protest. Nunn’s start into curating was as down to earth as she is: her first job was curating “fossilized poop” for a Pony Express station, and then she worked in retail for many years, learning display techniques. When she was a girl, Nunn collected everything from Barbies to sugar packs, winning a a prize at the Arizona State Fair for her panda collection, beating out the “Owl Lady.” Her unique background gives her the chutzpah, delight, and practical intelligence needed to create a welcoming environment for artists and the general public at the NHCC. Nunn’s current project, “A Room of her Own: My Mother’s Altar” is an art installation and collaboration with Sandra Cisneros, acclaimed author of The House on Mango Street and Caramelo. In the tradition of Dia de Muertos ofrendas, Cisneros originally created the piece immediately after her mother’s death and wanted to re-work it after her process of mourning, which is the subject of Cisneros’ upcoming novel. Nunn worked with Cisneros for three days. It was a “visual, intellectual, artistic, mourning and emotional process,” says Nunn. Cisneros found the perfect place for each piece “strategically, visually, sentimentally, artistically,” because, “everything has a meaning, everything.” The exquisite, brilliantly colored installation is filled with gifts for her mother, photographs, flowers, candles, suspended clothing. Cisneros paints two images of flowers (on the wall next to the acknowledgements) so her mother could finally have a piece of original art, writing directly on the walls, “They say that when someone you love dies, a part of you dies with them. But they forget to tell you that a part of them is born in you.” The installation evokes such strong, tender, transformative feelings in gallery goers that Nunn has held it over until November 2012. |

|

516 ARTS gallery installation mural

|

Suzanne Sbarge Suzanne Sbarge hesitates to use the word “curator,” saying there is “not a word for all the things I do.” Putting together a show at 516 ARTS utilizes Sbarge’s skills as a writer, editor, graphic designer, community organizer, public relations whiz, and fundraiser. She describes herself with the catch-all “arts organizer,” because her projects encompass so many community partners. She often includes different kinds of artists, from theatre companies to poets. Sbarge invites guest curators and fellow staffers to curate and to pitch ideas; many exhibitions are curated collaboratively. She says, “Because 516 is small and agile, we can rally forces together fast…to create things that no one organization could do alone.” This collaborative approach has become her trademark. For example, in Fall 2012, she is collaborating with Andrea Polli of the University of New Mexico (UNM), and so far, over 91 partner organizations, on “ISEA2012 Albuquerque: Machine Wilderness: Re-envisioning Art, Technology and Nature,” an international symposium, exhibition and regional collaboration on the subject of art, science and technology.

|

Sbarge is a collage artist, working with mixed media, combining paint, photographs, and a variety of found images and materials. With each piece, Sbarge creates cohesion, and allows space for wondering and imagining. She also sees her work at 516 ARTS as a kind of collage. With each exhibit she asks, “Why are these elements together? What is the logic or poetry in bringing these artworks, ideas and people together?” At 516 ARTS, she focuses on how art experiences bring people together and create dialogue, engaging the imagination and the intellect of the audience members. Like Nunn, Sbarge started curating as a child, making a little museum in the woods, using rocks as pedestals. Sbarge began to learn the skills putting together arts events and exhibits for Albuquerque’s Living Batch bookstore and Salt of the Earth Bookstore (both now sadly defunct). Her career took off when she became Program Director at the Harwood Art Center in 1995, later going on to direct Magnifico. When the McCune Foundation approached Sbarge about revitalizing Albuquerque’s downtown in a project that artists, audiences, businesses and government could rally around, 516 ARTS was born. Their focus is educational and community building—they bus in school kids, do a variety of community outreach efforts and cultivate involvement from local cultural and business leaders. It’s a mix Sbarge adores. 516 ARTS’ most popular projects include STREET ARTS (addressing graffiti and hip hop culture, which brought in their largest number of non museum goers ever), with UNM’s wonderful Land Arts of the American West program to create the LAND/ART collaboration (which received major articles in Art in America and The LA Times, among others). She says, “curating has become part of my art now…where I can make the biggest difference.” Johnny Salas New Mexican artist Johnny Salas started dreaming about a space of his own fifteen years ago, while working at the Historic La Posada Hotel in downtown Albuquerque. He didn’t think his goal was feasible until he exhibited his work at the New Mexico State Fair, which led to him being offered the upstairs space in Old Town he occupies today. At first, he exhibited only his own work. In order to fill the space with his relatively small, lavishly decorated, witty Santos altars, he felt like an exhausted “manufacturing machine.” Then he realized how many fabulous local artists he knew. Now fostering this community of artists through his gallery is his greatest joy. He loves that the people who come to Santisima regularly say they are “never disappointed,” and “always surprised.” All of the artists he represents have a very high level of craft, inspired by Dia de los Muertos and Santos imagery. The work in his gallery is inclusive of everyone, religious people, the gay community (check out Charlie Carrillo’s “Adam and Steve”), atheists, tourists (Salas says, “we are all God’s children”). Salas accepts that some find his gallery “shocking.” To him, the worst thing would be if someone left his space with “no impression.” His gallery can bridge a gap, people can learn about different cultures, become educated, even enlightened. Salas’ artists are from New Mexico, and their work is highly distinctive—rosaries with skulls to wear as necklaces for Dia de los Muertos: tattoo artists turned portrait makers, the Queen of South Broadway Goldie Garcia’s art pieces and famous bottle cap earrings; scrap metal salvaged and reinterpreted into beautiful altars by Kenny Chavez: postcards, prints and paintings by the talented Brandon Maldonado: fine art paintings by Manual Salas: and Johnny Salas’ own sparkling Santos—from Saint Anthony to the Santo Nino. Johnny Salas started making art during a cancer scare—fortunately a false alarm. His grandmother took him to the sanctuary of Chimayo, a powerful site for pilgrims in northern New Mexico. He was so moved by the power of the place that he started making his shadow boxes of the saints. When he was quite young, his grandmother told the children in his family to embellish their images of the saints with glitter, “to heighten the favor.” Salas truly believes that the Santos are here to help us. What is he excited about next? His gallery is so successful, garnering a celebrity clientele, appearing on the AMC hit “Breaking Bad,” that he could expand. He doesn’t rule out the possibility, but he loves the intimacy of his “little piñata” of a shop, that is “about to burst.” There is so much “eye candy” that people sometimes takes 45 minutes to see it all, circling the space 3-4 times. A lover of the live and in person gallery experience, he doesn’t have a website, he doesn’t spend much time on e-mail, he pays artists more regularly than other galleries, but he also loves that his gallery is thriving, precisely because he does things his own way. Three curators, three ways to cultivate soul in our community—what could be more fabulous? |

|

Elaine Avila is a playwright and art critic and holds the Robert F. Hartung Endowed Chair of Dramatic Writing at the University of New Mexico. Originally appeared in The Collector’s Guide - Volume 26 |

Collector’s Resources |

|

RESOURCE LISTS UPDATED WHEN VIEWED | ARTICLE CONTENT REVISEDJuly 24, 2012 |