A Sacred Place: Meditations on Corn

|

|

We awoke as the first colors of the day danced themselves across the smooth mud walls of our house and traveled toward the corn fields at the west end of the village: Village Where Roses Grow Near Singing Water. Under our soft, woven blankets, insulated from the cool fall air that had crept in mountain lion-like as we slept, we pulled ourselves from our dreams and waited for the sun.

Taking turns with a small spiny brush made from dry yucca leaves, we smoothed and twisted each other’s hair into little butterfly shapes, and tied them into place with thin strips of smoked elk hide.

The butterfly shapes were the color of storm clouds at night.

We dressed ourselves in the thick wool mantas and wide woven belts made for us by Gia, and helped each other with our tall, white moccasins, whose black soles curved upward at the tip.

We made our sakewe from the corn that we ground into fine meal, and water from a small spring near the river. We ate sakewe every morning.

We also used the corn meal for praying.

Maize, from the Arawak Indian word marise, or corn as we know it today, is believed to have come to Turtle Island from the tribes of Mexico and from the Carib of the West Indies. As it proved relatively easy to cultivate and was quite prolific in both quantity and variety, it became a staple food source for cultures throughout the Americas.

From what eventually became known as Indian corn, many colorful foods were coaxed forth: piki bread, blue corn porridge, succotash, hominy, ash cake, pancakes, corn stew. |

|

The fields were many steps from our house, and we walked slowly in their direction.

Above us, white geese; to the north, thick clouds and mountains; all around us moist air and light.

Stepping into the dampness of the bright green rows, moving toward the center of the sunlit maze, we brushed against the dry corn blooms that poured from their stalks and made low rustling sounds when birds or wind moved near them. And when birds or wind moved near them and the corn blooms made low rustling sounds, we knew the corn was ready for harvest.

Gently we plucked the large, plump pods from the slender plants and piled them at the end of each row. As each pile grew, patiently marking the passing of the day, it spilled over into the next, and that one into the next, swallowed by each other, until there was just one, large enough to redefine the borders of the maze.

For several days the corn dried in the air and sun, and when we returned to the field it was the color of verylight sandstone, the same as that which lined the canyon walls to the east.

Each of us set out a large blanket and bundled the corn within. The withered husks, twisted into gracefulshapes by the wind, tossed against each other as we carried the bundles home; the sound of reeds in rushing water.

Late blooming cactus grew along the edges of the narrow road that led from the field, and there were many low-lying vines that were thick with green and yellow gourds. Beyond the road, where the land moved away from us, small collections of tall yucca plants grew, and beyond them, closer to the river, several thin rose bushes had pushed up through the hard soil.

A grove of cedar trees stood ahead of us, near the winter kiva, and sweet grass was all around. In spring there were eagles here.

Looking toward the west, a wide sandy plain curved into the distance, eventually disappearing from our sight. Ant mounds of different sizes rose out of the otherwise flat ground: a constant movement of red and black on the stillness of the land.

We often gathered plants of many kinds there, where the plain curved. It was a sacred place. |

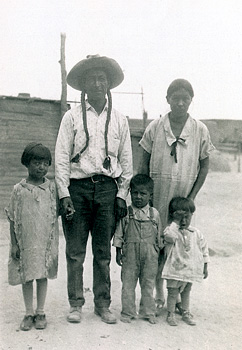

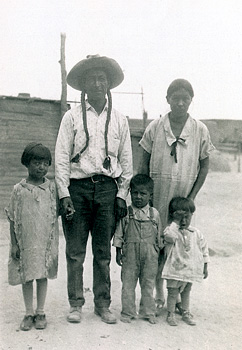

Author RoseMary Diaz' great-grandparents Jose Victor and Christina Naranjo with children. Santa Clara Pueblo ca. 1927

|

Corn also holds great ceremonial value among many indigenous societies, and is used in various dances, celebrations and rites of passage. Among the Southwest Indians, particularly the Hopi and Tewa, corn is intertwined with virtually every aspect of life: infants are fed fine cornmeal during naming ceremonies; it is offered in daily prayer; it sustains us through our earthly physical lives; it nourishes our spirit in the next world.

Feast Day at Santa Clara Pueblo, celebrated each August, always includes a corn dance. Two rows of dancers, alternating male female, move in perfect timing, weaving in and out of each other, surrounded by drums, gourd rattles and corn songs.

Shadows cast by the dancers on the soft sandy ground resemble the movement of cornstalks in wind. The corn bundles carried by the women are rubbed with sacred mud and tied with dried husks and evergreen sprigs. These are the gifts of the corn maidens, and will be planted in the spring.

|

|

We did not speak as we walked past the kiva; drum sounds and voices echoed from within its walls and filled the space between us. We shifted the weight of our corn bundles; again, the sound of reeds.

Red willows sprang from beneath the cottonwood trees that marked the center of the village, and swayed in circular patterns as soft breezes from the north fluttered around them. We had danced there, near the willows, many times.

The road thinned and wound down through a small orchard planted with peach and plum trees, branching off in several directions, then continuing on beyond us. We stayed to the north, walking toward our home, and toward blue clouds.

Lightning flashed above the mountains, where kachinas lived and morning glories twined over the cliffs. Various shades of grey pushed through the blue, sending shadows into the sunlight and drawing the clouds closer to us. Thunder traveled down the canyons and into the village, where it turned to silence again.

We prayed for rain.

Setting our bundles on the cool ground in front of our house, we hoped for many colors of corn.

Gently we peeled away the papery husks, uncovering the rows of shiny seeds within, and sorted them according to color, each representing its own direction, its own color of cloud, its own color of butterfly. Some people in the village were named after these colors.

We set aside some of each to grind into fine powder and some for dances, and stacked what remained in long flat rows inside our house, against the edges of the warm walls. What we ground we mounded into clay pots of different shapes and sizes, some with black obsidian-like finishes, some earth colored, and some painted with bear paw, parrot feather or avanyu designs.

A few we left in their husks, and braided the leaves of three or four ears together. We hung them on the east wall near where we slept.

Standing in the center of the room, we were surrounded by corn. This was a sacred place. |

Technology continues to bring forth new uses for corn and corn-derived products, while indigenous peoples hold steadfast to its traditional roles.

In recent years, several seed-exchange programs have been developed, most notably that created at Cornell University, in an effort to reintroduce ancient strains of corn from throughout the Americas. This follows a seemingly inherent need to root ourselves to that which defines and sustains us, and perhaps a desire to return to mother corn as guardian of the people. |

|

Gathering the husks back into the blankets, we returned them to the field. We smoothed them out in a thin even layer over the just-harvested rows, along the base of the still-standing stalks, to protect the soil from early frosts and late snows.

Soon the stalks would fall into the thin layer of husks and disappear into winter, and the cycle of the corn would be complete.

Clouds gathered from all directions. They swirled into and pushed against each other, and their shapes changed as they moved through the sky; centers stretched into edges; edges pulled back into centers.

A thin layer of yellow light weaved itself through the blue air above us, sending long, thin shadows onto the ground.

Walking homeward again, we thought of the creation stories told to us by Ta’a; how our people came from the north, the place of emergence, and traveled down mountains and mesas and across flat, grass-covered prairies and though deep rivers and shallow streams and over watery marshes thick with cattails and around frozen clear lakes and past deep caves and under juniper trees heavy with berries and into snow-filled forests.

They traveled in accordance with the positions and movements of stars, and listened closely to the wind currents that spun about them.

This was the time of learning and of naming things, and the people gathered great knowledge from all that surrounded them. They named trees and mountains and hills and clouds; they named reflections in ponds and spirals in fine dirt; they named animals and plants and colors of clay; they named patterns of bird tracks near the river’s edge; they named the different sizes of raindrops; they named the sounds of rustling leaves; they named the taste of tree sap and the texture of salt; they named the motions of sand swirling in stream-side springs; they named the different shades of light around the moon.

Waves of cool air rushed over us as the sun moved toward the horizon and sank down

into dusk. The lightning and thunder grew brighter and louder, and the wind’s shrill wolf-songs floated above then passed into the coming darkness.

Reaching the low, narrow doorway of our house, we were happy to be home, near Gia and Ta’a, again.

We went inside and waited for the rain.

This was a sacred place too.

Thanks to RoseMary Diaz, an author, poet and freelance writer living in Santa Fe. On our site you can also read RoseMary's Poetry of the Pueblo Dances.

Originally appeared in The Wingspread Collector’s Guide to Santa Fe, Taos & Albuquerque – Vol 21

|

A Small Glossary

Gia (Gee-ah; g pronounced as in gem, long e) Mother

sake’we’ (sah-keh-weh, all short vowels) a porridge made from finely ground blue corn meal

piki (pee-kee, all long vowels) a very thin, paper-like bread made from cooking a mixture of corn meal and water, and sometimes a bit of ash, on a hot stone

kiva (kee-vah, long e, short a) a ceremonial chamber, traditionally round and underground, used by the Pueblo Indians of the American Southwest

kachinas (ka-cheen-ahs, hard k, long e, short a) ceremonial wooden carvings representing the many deities, gods and spirits held sacred by the Pueblo Indians

avanyu (ah-vahn-yoo, all short vowels) plumed water serpent figure; used by the Tewa in decorating pottery, textiles and baskets

Ta’a (T pronounced almost like a d, short a sounds) Father

|

|